Leverage products

Warrant

Leveraged products are financial instruments that enable traders to gain greater exposure to the market without increasing their capital investment. They do so by using leverage.

Any financial instrument that allows you to take a position that is worth more on the market than your initial outlay is a leveraged product. Different leveraged products work in different ways, but all amplify the potential profit and loss for a trader.

Leveraged products will almost always require you to pay an initial portion of the position you intend to open. This is called the margin.

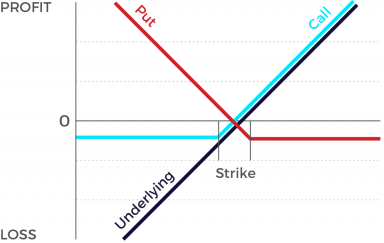

Market expectation

- Warrant (Call): Rising underlying, rising volatility

- Warrant (Put): Falling underlying, rising volatility

Characteristics

- Small investment generating a leveraged performance relative to the underlying

- Increased risk of total loss (limited to initial investment)

- Suitable for speculation or hedging Daily loss of time value (increases as product expiry approaches)

- Continuous monitoring required

Graphic

Perhaps it’s easiest to explain the way warrants function by applying an example from everyday life. Imagine there’s an outstanding Italian restaurant in your neighborhood, and you’re one of their most loyal customers. As a gesture of gratitude, the proprietor sells you a couple of gift certificates for dinner valued at CHF 15 for the special price of CHF 10. They’re valid for two years’ time, and the normal price these days for a meal is CHF 12.00. Because you’d save CHF 2 by using the gift certificate today, it essentially has a value of CHF 2. So let’s call that value the “intrinsic value” of the certificate. Six months later, the restaurant finds it necessary to hike the price of a meal because increasing wage costs and energy prices leave it no other choice, so now a dinner costs CHF 14, 16% more than a while back. But with your gift certificate, you can still enjoy a meal for CHF 10.00. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out that the certificate now has an intrinsic value of at least CHF 4. In other words, its value has risen by 50% - much more than the percentage increase in the price of a meal. Thus the gift certificate has experienced “leverage” because of the price change. Ah…but imagine that the price of a meal suddenly dropped to CHF 10.00. At least for the time being, your gift certificates would be worth nothing because they offer you no advantage over a direct purchase of the meal. But would you simply throw them away? Probably not, because as long as they remain valid, the possibility still exists that the restaurant owner will opt to raise his prices, at which point the certificates would have value again. So as you can see, it’s not just intrinsic value that plays a role in such a gift certificate - there’s also a kind of “time value” involved. That time value is a reflection of the likelihood (or lack thereof) that the certificate will gain in value at some point before it’s term of validity runs out.